Konrad Schneider is the namesake of Schneider Prairie. Although Schneider was a early settler in the Griffin area, he was not the first white settler of what became known as Schneider Prairie.

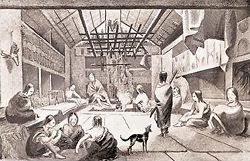

Schneider Prairie is one of several oak prairies that existed in Thurston County. Oak prairies were very important to Native Americans. They periodically burned the underbrush on these prairies to keep them open, which attracted deer that were hunted. Native Americans also harvested camas, berries, and acorns on the prairies.

Early white settlers sought these prairie areas for their land claims. Prairies were desirable since they were already cleared to a substantial extent and had relatively good soils.

Puffer and Cross

Two early white settlers filed separate donation claims for the same 160 acres of land on Schneider Prairie. Griffin School, the old Haller mink farm, the Grange Hall, the golf driving range, and the Island Market are located on this claim.

The northern boundary of the claim was about where the Prosperity Grange Hall is located, and where Sunrise Beach Road enters Steamboat Island Road. The eastern boundary was approximately where Mink Street first meets Sunrise Beach Road. The southern boundary was located on about 33rd Street. The claim had about 150 feet of frontage on Eld Inlet. The western boundary was west of the freeway overpass over Highway 101.

William W. Puffer may have been the earliest white settler on Schneider Prairie. He filed a donation land claim for this acreage on April 17, 1855. Field notes from the original survey of the Griffin area on August 4, 1855 noted Puffer’s land claim, with 10 acres under cultivation, and a house. The house was located at about the corner of Sexton Road and Steamboat Island Road. The cultivated area was west of the cabin. However, the Puffer claim was not successful.

Benjamin Franklin Cross filed a claim for the same land on August 26, 1855. Interestingly, Puffer attested on April 17, 1856, that Benjamin Cross had resided on the claim since August 24, 1854. Cross was born in New Hampshire in 1832. He was a resident of Sawamish (Mason) County at the time of filing his claim. An affidavit by Cross indicated that he was single, had arrived in Washington Territory on November 3, 1853, and had first settled on the land claim on August 26, 1854. A 1858 survey of the area noted that Cross resided in the former Puffer cabin.

The original 1855 survey of the Griffin area noted two white (Gerry or Oregon) oaks, 18 inches in diameter, to locate a section boundary line cutting across the property. These markers are called "bearing trees". One, known as the historical Schneider Prairie Oak Tree, still stands, and currently has a diameter of 60 inches. It is located west of the old barn on Schneider Prairie. Only a stump remains of the second bearing tree.

Cross sold his donation land claim to Eli Montgomery in 1862. Previously, Montgomery acquired a donation land claim for property located on the southeast portion of Mud Bay. He also acquired 33 acres of waterfront land west of the Cross donation land claim on the dead-end portion of what is now Madrona Beach Road. Montgomery sold the Cross donation land claim, and the 33 acre parcel, to Konrad Schneider in 1866.

Schneider and Solbeck

Konrad Schneider was born in 1818 in Hessen, which is now part of Germany. His wife (Albertina) was born in Sweden in 1830. They met and were married in Burlington, Iowa, in 1852, and soon left for Puget Sound in a covered wagon.

Schneider was a stone mason and had been awarded a contract to build a lighthouse at Dungeness near Port Townsend. They arrived in Tumwater in the fall of 1852. Schneider acquired a donation land claim for land located on what is now Case Road, south of the Olympia Airport and north of Millersylvannia State Park.

Konrad and Albertina had nine children -- Henry (born in 1853), August (born 1855), Catherine (born 1857), Molkina (born 1859), Frederick (born 1862), Konrad (born 1864), Matilda (born 1867), William (born 1871), and Albert (born 1874). Many of their descendants still live in Thurston County.

Konrad Schneider built the first bridge across the Deschutes River in Tumwater. He also "built or cut" a trail from McLane Crossing on the west bank of Mud Bay out to his property on what became known as Schneider Prairie. Presumably, much of this trail followed the northern portion of an old Indian trail from Black Lake to the southwest shores of Mud Bay. McLane Crossing is near the junction of MacKenzie Road and Delphi Road.

Konrad Schneider acquired additional acreage south and west of the Cross donation land claim, including a homestead of 107 acres in 1882, up what is now called Whittaker Road. The family referred to this valley as Schneider’s valley. A short poem about this land was often recited at family gatherings -- "I'll rally, rally. Everybody’s happy in Schneider’s Valley."

August Schneider purchased property in 1878 located south of the Cross donation land claim along Eld Inlet, extending south to where the old Ellison Oyster Company was located. A few months later, August sold this property to his sister Molkina, who was married to Swan Solbeck. Swan Solbeck was enumerated as being a farmer on this property in the 1880 Territorial census. A rock quarry was operated on the Solbeck property, beginning in at least 1889. Rock was taken down to Eld Inlet where it was hauled away by barge. This quarry operation lasted for decades. Remnants of the quarry can be seen on the tall rock bluff that is located west of Highway 101, just south of the entry to the highway from the Griffin community, off what is called Old Highway 101.

The Schneider family was enumerated in the 1871 and 1873 Territorial censuses in the Griffin area. However, his sons Henry and August are enumerated separately in the 1880 Territorial census as living in the Griffin area. Konrad is listed with his son Henry. This may mean that Albertina was residing on property located on the west side of Budd Inlet, near the old lumber mill, on what is now Westbay Drive. These holdings included considerable acreage on the top of the hill to the west where the family had an orchard.

Konrad Schneider sold two acres of land to Schneider Prairie School District in 1885. This land was located about where what is now Whittaker Road meets Highway 101, south of the overpass across Highway 101. A schoolhouse was constructed at this site to accommodate an increased number of students attending school in the Griffin area. Originally, school was held in the John Olson cabin, located in what is now Holiday Valley Estates. The children of John and Elizabeth Zandell, and Thomas and Mary Kearney, attended school in the Olson cabin. The Zandells and Kearneys owned land claims on Oyster Bay, west of the Olson land claim. A larger school facility was needed when the children of Swan and Molkina Solbeck became of school age.

Konrad Schneider died in 1903. His heirs sold their interests in his Griffin-area property to his son-in-law and daughter, Swan and Molkina Solbeck. The Solbecks sold their Griffin-area holdings to Judge Arthur E. Griffin and Gabrielle Griffin in 1918.

The Schneider Prairie schoolhouse burned to the ground in the summer of 1926. Children in grades 5 through 8 attended school in the old, two-story Prosperity Grange Hall located on the site of the current Grange hall. Children in grades 1 through 4 attended school in the old Frye Cove School District schoolhouse, which was reopened. This abandoned schoolhouse was located near what now is Gravelly Beach Road, at the top of the hill, west of the Griffin fire station at the corner of Gravelly Beach Loop and Young’s Road. The Griffins essentially gave the school district a new five acre school site, where Griffin School is now located, by exchanging this property for the two acre lot where the old schoolhouse was located. Schneider Prairie School District was renamed the Griffin School District in honor of this generous act. A new, brick schoolhouse was build on the new school district property. The new facility opened in the spring of 1927.

-- STEVE LUNDIN

Copyright 2008 by Steve Lundin

Steve Lundin is a long-time resident of the Griffin community located in northwest Thurston County. He received a B.A. degree from the University of Washington and a J.D. degree from the University of Washington Law School and recently retired as a senior counsel for the Washington State House of Representatives after nearly 30 years.

He is recognized as the local historian of the Griffin area and has written a number of articles on local history and a book entitled Griffin Area Schools, available from the Griffin Neighborhood Association at a cost of $10.

Lundin also wrote a comprehensive reference book on local governments in Washington State entitled The Closest Governments to the People – A Complete Reference Guide to Local Government in Washington State. The book costs $85, plus shipping and handling. It is available on the web from the Division of Governmental Studies and Services, Washington State University, or from WSU Extension.

This is part of a short series of papers on local history. The first of this series was published last month. Click here to read "Griffin Historical Sketch."

If you have old historic photos of the Griffin area, or family stories of the old days in the Griffin area, please contact Steve Lundin at s.lundin@comcast.net. Steve is most interested in photos of the old two-story Grange Hall in the Griffin area and the old Schneider's Prairie schoolhouse that burned to the ground in 1926.

he Griffin community is located in northwest Thurston County and occupies the Steamboat Island peninsula that extends northward into southern Puget Sound.

he Griffin community is located in northwest Thurston County and occupies the Steamboat Island peninsula that extends northward into southern Puget Sound.